Tagged: nature-reserve

Whistle Stop Tour Via a Hansom

12 May 2021

I wanted to take another snap of an interesting Gothic Revival place in Clifton, having found out a bit more about the owner. On the way I walked through the Clifton Vale Close estate, idly wondering again whether it might've been the site of Bristol's Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens (I've not researched further yet.) On the way back I knocked off the last remaining bit of Queens Road I had yet to walk and tried to find the bit of communal land that Sarah Guppy bought so as not to have her view built on...

Leftovers with Lisa

01 May 2021

I didn't get to all the little leftover streets around the northeastern part of my area in today's wander, but I definitely knocked a few off the list, plus Lisa and I enjoyed the walk, and didn't get rained on too badly. We spotted the hotting-up of Wisteria season, checked out Birdcage Walk (both old and new), ventured onto the wrong side of the tracks1 and generally enjoyed the architecture.

1 Well, technically we probably shouldn't have been on the grounds of those retirement flats, but nobody started chasing us around the garden with a Zimmer frame

The Mall Gardens

19 Apr 2021

Just a quick errand to the Post Office to send off Mollog's Mob, but afterwards I bought a flat white and a new plant from Foliage Cafe and headed for The Mall Gardens to enjoy sitting in the sun and reading a book on the first day this year that's been properly warm enough for it. Nice.

The Mall Gardens does actually have some signs up letting people know it's a public garden, but I think it was only my researches for this project that brought the number of public gardens there are in Clifton to my attention, and reminded me that I could make use of this space in Clifton Village, a little closer to the coffee shops and a little more sheltered than Clifton Down.

Quick Around-the-Harbour Wander with Lisa

20 Mar 2021

My friend Lisa was meeting another friend for a walk near the suspension bridge, so we fitted in a quick harbourside loop from my place first. We discussed gardening (we're both envious of the gardening skills of the Pooles Wharf residents; we can just about keep herbs alive, whereas they're growing heartily-fruiting lemon trees outdoors in England along with everything from bonsai to magnolias), cafes, work and architecture, among other things.

I lived near here when I first moved to Bristol in the mid-1990s. I never had to say the name of the street out loud, but it always reminded me of "GELF" back then—the Genetically Engineered Life Form that was a monster-of-the-week in a couple of Red Dwarf Episodes.

Having just done the tiniest bit of research after noticing while looking at maps that a section of harbourside here used to be Gefle Close, I found out a couple of things that make me feel a bit dim now: It's pronounced, as near as I can work out, "Yev-leh", not "geffel", and it's a port in Sweden, more properly spelled "Gävle", apparently.

Which makes a lot of sense, given that this street is on the Baltic Wharf housing estate, on the site of the wharves where apparently a lot of things from that area were imported and unloaded, especially timber, though Gävle seems to be more well known copper and iron.

It seems Gävle is pleasantly green and widely-spaced these days, having had major fires rip through it three times in the last three hundred years, and finally rebuilit itself with big espanades and a larger grid system with firebreaks. Sounds nice.

I went to get my first dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine today. Handily, the vaccination centre was Clifton College Prep School in Northcote road, next to Bristol Zoo, a road that's just within my 1-mile range that I hadn't visited before.

I parked up near Ladies Mile and tried to find a few of the tracks marked on the map I'm using, but couldn't see most of them. Whether that's just because they've disappeared over time, or with the recent lack of use or waterlogging from the 24 hours of rain we just had, I'm not sure. It was a pretty fruitless search, anyway.

The vaccine shot was virtually the same setup as when I got my winter flu jab back in November, except for the venue. I snapped a couple of pictures of the school while I was there, but I was in and out in five minutes, and you probably don't want to linger around a vaccination centre, I suppose.

Instead I wandered around the compact block of the Zoo, now sadly scheduled for closure. By coincidence I finished E H Young's Chatterton Square this morning: set in Clifton (fictionalised as "Upper Radstowe") near the Zoo, the occasional roars of the lions that can be heard by the residents of the square (Canynge Square in real life) form part of the background of the novel. The book's set in 1938 (though written and published post-war, in 1947). It seems a shame that the incongruous sounds of the jungle will no longer be heard from 2022. All I heard today were some exotic birds and, I think, some monkeys.

I was told not to drive for fifteen minutes following the jab, so I wandered out of my area up to the top of Upper Belgrave Road to check out an interesting factoid I'd read while looking into the history of the reservoir at Oakfield Road, that the site of 46 Upper Belgrave Road was a bungalow, shorter than the adjacent houses, and owned by Bristol Water, kept specifically low so that the pump man at Oakfield Road could see the standpipe for the Downs Reservoir (presumably by or on the water tower on the Downs) and turn the pump off when it started overflowing. Sadly I couldn't confirm it. There is one particularly low house on that stretch, but it's number 44, and though small, it's two-storey, not a bungalow, so nothing really seems to quite fit in with the tale.

I'm writing this about nine hours after getting the jab, by the way, and haven't noticed any ill effects at all. My arm's not even sore, as it usually would be after the normal flu jab. In twelve weeks I should get an appointment to get the second dose.

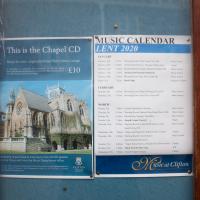

Must've been the last event planned. I wonder how far they got through the programme? Tuesday just gone was Shrove Tuesday this year, and the first lockdown started (for me, at least) on 17th March 2020.

I got interested in Bristol's medieval water supplies after poking around near Jacobs Wells Road and Brandon Hill. It was during that research I found out about a pipe that's still there today, and, as far as I know, still actually functioning, that was originally commissioned by Carmelite monks in the 13th century. They wanted a supply of spring water from Brandon Hill to their priory on the site of what's now the Bristol Beacon—Colston Hall, as-was. It was created around 1267, and later, in 1376, extended generously with an extra "feather" pipe to St John's On The Wall, giving the pipework its modern name of "St John's Conduit".

St John's on the Wall is still there, guarding the remaining city gate at the end of Broad Street, and the outlet tap area was recently refurbished. It doesn't run continuously now, like it did when I first moved to Bristol and worked at the end of Broad Street, in the Everard Building, but I believe the pipe still functions. One day I'd like to see that tap running...

There are a few links on the web about the pipe, but by far the best thing to do is to watch this short and fascinating 1970s TV documentary called The Hidden Source, which has some footage of the actual pipe and also lots of fantastic general footage of Bristol in the seventies.

On my walk today I was actually just going to the building society in town, but I decided to trace some of the route of the Carmelite pipe, including visiting streets it runs under, like Park Street, Christmas Street, and, of course, Pipe Lane. I also went a bit out of my way to check out St James' Priory, the oldest building in Bristol, seeing as it was just around the corner from the building society.

There are far too many pictures from this walk, and my feet are now quite sore, because it was a long one. But I enjoyed it.

Snowy Leigh Wander

24 Jan 2021

I started this wander with my "support bubble" Sarah and Vik, after Sarah texted me to say "SNOW!" We parted ways on the towpath and I headed up into the bit of Leigh Woods that's not actually the woods—the village-like part in between Leigh Woods and Ashton Court, where I'd noticed on a map a church I'd not seen before. I found St Mary the Virgin and quite a few other things I'd never experienced, despite having walked nearby them many, many times over many years, including a castellated Victorian water tower that's been turned into a house...

Leigh Woods Solo

19 Jun 2021

I hadn't really planned to go out for a wander yesterday; I just got the urge and thought "why not?" (Well, the weather forecast was one possible reason, but I managed to avoid the rain, luckily.)

I wanted to finish off the A369—as it turns out I may still have a small section to go, but I've now walked the bulk of it out to my one-mile radius—and also a few random tracks in Leigh Woods. I'm still not really sure that I'm going to walk them all, especially after discovering today that "the map is not the territory" applies even more in the woods, where one of the marked tracks on the map wasn't really that recognisable as a track in real life... I'm glad I'd programmed the route into the GPS in advance!

Anyway. A pleasant enough walk, oddly bookended, photographically at least, by unusual vehicles. Leigh Woods was fairly busy, especially the section I'd chosen, which was positively dripping with teenage schoolkids with rah accents muttering opprobrium about the Duke of Edinburgh. I'm presuming the harsh remarks were more about taking part in his award scheme than the late Consort himself, but I didn't eavesdrop enough to be certain...

Victoria Square Underpass

06 May 2021

I'm meant to be taking a little break from this project, but in my Victoria Square researches after my last walk I noticed a curiosity I wanted to investigate. The community layer on Know Your Place has a single photograph captioned, "The remains of an 'underpass' in Victoria Square".

Looking back through the maps, I could see that there really did used to be an underpass across what used to be Birdcage Walk. I can only guess that it was there to join the two halves of the square's private garden that used to be separated by tall railings that were taken away during WWII. Maybe it was a landscaping curiosity, maybe it was just to save them having to un-lock and re-lock two gates and risk mixing with the hoi polloi on the public path in the middle...

Anyway. Intrigued, I popped up to Clifton Village this lunchtime for a post-voting coffee, and on the way examined the remains of the underpass—still there, but only if you know what you're looking for, I'd say—and also visited a tiny little road with a cottage and a townhouse I'd never seen before, just off Clifton Hill, and got distracted by wandering the little garden with the war memorial in St Andrew's churchyard just because the gate happened to be open.

EDIT: Aha! Found this snippet when I was researching something completely different, of course. From the ever-helpful CHIS website:

When there were railings all round the garden and down the central path, in order that the children could play together in either garden there was a tunnel for them to go through. This was filled in during the 1970s but almost at the south east end of the path if one looks over the low wall the top of the arches can still be seen.

This is more convincing as a walled-off underpass entrance. You can see there's a sheet of steel that's been placed in front of what looks like an entrance before it's been buried with earth.

Gardens and Cottages

17 Dec 2020

I think the cute little Duncan Cottage was my favourite bit of this wander up the hill to get coffee and a pain-au-raisin from Twelve, though I did enjoy gently musing on the public and private gardens of Clifton, inspired by a closer pass than usual to Royal York Crescent's garden.

I managed absent-mindedly to clear my GPS track before saving it, so this hand-created track-log may cause me problems in the future. I suppose we'll see.